Clik here to view.

This week, I’ll be talking about Twitter

Twitter is a well known microblogging platform. People can post updates in the form of 140 character “tweets” that can be read by followers, who can “retweet,” i.e. repost that tweet to their own followers, or reply to the original post. I started using it about a year ago, and have found it to be equal parts whimsical and hilarious, along with useful and informative.

Several other authors have discussed reasons why scientists should be using Twitter, including this excellent post on Deep Sea News and this post through the American Geophysical Union. For a more personal opinion, Dr Jeremy Segrott gave his thoughts after he used Twitter for a three months. Scientists are realizing that social media is an important way to translate knowledge to the public when done well, and Twitter provides another avenue by which this can be accomplished.

What I will do is post 5 reasons why I think, as a scientist, you should be using Twitter, or, at the very least, be signed up for a Twitter account. Over the next three posts, I’m going to cover five reasons why I think you should use Twitter, and how it can be incredibly useful as a networking tool. Reasons 2 and 3 will be up on Wednesday, and reasons 4 and 5 will go up on next Monday. I’m not going to go into details about how to set up a Twitter account, and will instead link to some Twitter 101 guides to help you get started at the end of this post. However, before we start, I’m going to cover some terms I’ll be using so everyone is on the same page.

- A “tweet” refers to a message up to 140 characters in length. This is the message that you write.

- A “hashtag” is a Twitter based “filing system.” Within Twitter, people can use hashtags to categorize tweets. So, for example, tweets about graduate school use the #gradschool hashtag; Tweets about Kingston (the town I live in) use the #ygk hashtag. It means that anyone who wants to find Tweets about Kingston can search #ygk, and as long as the original person used that tag, they’ll be able to find it. Other popular tags include #scied, for science education, #phdchat for discussions around PhD-related issues, #madwriting for people who are trying to bust through a writing slump, and #TMLtalk for those with terrible taste in hockey teams. Events such as the #GoldenGlobes also have their own hashtags, and you’ve probably seen hashtags at the bottom of your screen while watching the news, or even TV shows.

- “Retweeting” refers to when you repeat what someone else has written, giving them credit. This can occur either through a direct retweet (using the retweet button), or by adding a comment and the letters RT before the original tweet. Sometimes you have to cut down the number of words used if you want to add a comment in front of their tweet, and so the acronym MT (modified tweet) is used to indicate that you have changed their original tweet.

Reason #1: It has very direct, and very relevant implications for those in Public Health

Everyone has a cellphone; some people have two. With the advent of social media (i.e. Facebook, Twitter etc), we are sharing more than we ever have in the past, and anyone can know about that awesome new app that I found, or the delicious Christmas dinner I made. However, while personal tweets can be frivolous, using them to track when people report symptoms of being sick is something that Epidemiologists can use. You imagine the number of “I hate being sick!” and “My nose is stuffed up!” tweets people write in the winter and you know what I mean. This is a very rich, but very poorly understood data source. There has been some exploratory work in this area. A researcher at LSU looked at the accuracy of using Twitter as a predictor of influenza outbreaks, finding that it was quite accurate, as the graph below shows.

Clik here to view.

Figure 2: Fitted and predicted ILI rates. The red line is predicted rates, the black line is the actual rate. The vertical line separates training from predicted data. (Culotta, 2010)

This is a new area however, and of course, this still needs work:

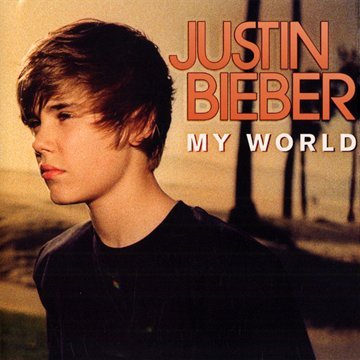

These results show extremely strong correlations for all queries except for fever, which appears frequently in figurative phrases such as “I’ve got Bieber fever” (in reference to pop star Justin Bieber).

Thanks to Jessica S. for that paper Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Another example of researchers using Twitter is investigating how misinformation spreads through social media. Misinformation bothers us, and it is something Beth has discussed over at Public Health Perspectives, as well as our own Cristina Russo here at Sci-Ed.

Researchers at Columbia sampled 1000 tweets that mentioned antibiotics to investigate how they were reported on Twitter. While the vast majority of tweets were innocuous, there were some that were clearly incorrect or misinformed. What is important however is the reach of these tweets: while 302 tweets by 277 individuals incorrectly used the words “cold” and “antibiotics” together, those tweets reached 850,375 followers (although this number is heavily skewed; the median number of followers was 66).

Clik here to view.

Rest assured readers, Bieber fever is not a contagious disease | Photo via Amazon.com

Come back on Wednesday for Reasons 2 and 3!

For a guide about how to set up a twitter account, I’d recommend the following links for a handy “how-to”: Wikihow, CNet, Brent Ozar’s FAQ, as well as Travis Saunders’ post about Twitter etiquette. If you’re wondering who to follow, I’d recommend checking out these lists: Colby Vorland’s list of Nutritional and Health Science people, Health Scientists, Shelley Wallingford’s list of Epidemiologists, Sara Caldwell’s Science-y Folk, RenuShenu’s Public Health Tweeple, Melonie Fullick’s PhDChat and Liz Ditz’s MedSocialMedia.

References:

Scanfeld, D., Scanfeld, V., & Larson, E. (2010). Dissemination of health information through social networks: Twitter and antibiotics American Journal of Infection Control, 38 (3), 182-188 DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.11.004

Culotta, A. (2010). Detecting influenza outbreaks by analyzing Twitter messages Unpublished. Available online at: http://www2.selu.edu/Academics/Faculty/aculotta/pubs/culotta10detecting.pdf

Ed note: A version of this series originally appeared on Mr Epidemiology (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3)

The post Twitter for Sci-Ed Part 1: Teaching in 140 characters or less appeared first on Sci-Ed.